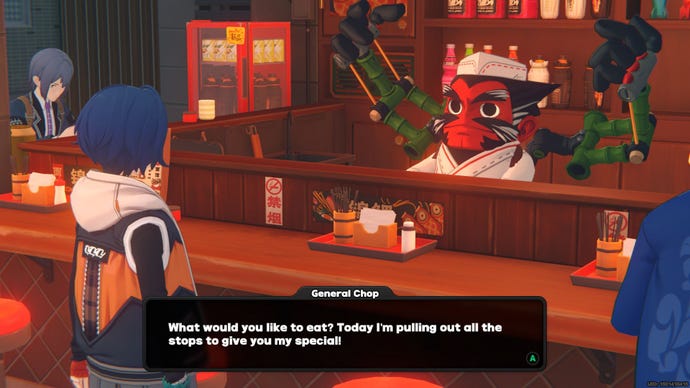

Many years ago, game designers advised their colleagues, make their prototypes “juicy”. They were talking about the nebulous collection of sensations the player is exposed to as heads explode, coins clink, and balls bounce. Zenless Zone Zero is a game deeply inspired by the philosophy of juice. Like the lootbox vendors of yesteryear, gacha designers understand the charm and power of a nicely animated gadget, opening up into pieces and bursting with potential. This pop visual and aural language extends to Hoyo’s latest game, from its cinematic moments, to each character’s attacks, to the adorable bunny mascots that explode with gatling guns, to the barista’s coffee-making ritual and the waiter’s robot-limbed noodle recipes. The menu screens, the maps, the free-to-play store, everything. It’s all very juicy. It’s pumped full of juice, but only in the same way that a chicken in a supermarket is pumped full of water.

The sci-fi city of New Eridu is plagued by giant domes of noxious matter that swell over entire neighborhoods, displacing citizens, spawning monsters, and rendering parts of the city impassable. Impassable, that is, except for your crew of three marauders who dive into these noxious “Hollows” to perform various favors for those outside. You can rescue trapped citizens, find lost hierloom, or search for a missing delivery driver. What it looks like (apart from an incoherent and overly long tutorial) is a third-person character action brawler combined with a grid-based exploration minigame with some very gentle sokoban puzzles, all wrapped up in a chunky free-for-all slot machine of characters and power-up candy.

The character’s combat action looks as frigid as anything in the genre. When my giant bear construction worker slams his giant pneumatic tool into an enemy’s head, it’s palpable, jarring. When a cyborg gunslinger pirouettes through a trio of glowing monsters, firing off scattered shots with the satisfying pop of microwave popcorn, it’s undeniably ill, awesome, AND gnarly. At special moments, you can switch characters to perform fluid, violent, transitional combos. Defying an incoming enemy attack (communicated by a flashing crosshair blink) explodes into a character-swap moment of spinning mega-action camera. Each fight unfolds with stylishly planned efficiency as you combine up-to-date characters to see what off-the-wall combos can look damn sweet.

Unfortunately, most of your time isn’t spent on combat. At least not in the early game’s story mode. And even later, when you spend more time on brawls, you’ll find that too much “cool” can be downright exhausting. Once you put aside how good it looks, combat can essentially be reduced to mashing the same four or five buttons in cycles without a huge need for strategy. The combat lacks much depth, being slick and superficial, filled with elegant enemies that often move as confidently as your characters but don’t stand out from each other in any mechanically meaningful way. So what is a game if not combat? Theft. elderly questionWhere is the game located?

Well, a lot of it involves going from menu to menu, clearing the red exclamation marks from the corners of the tab headers. It’s a sort of sweeping process that involves clicking “claim” wherever you can find them, dusting off various currencies with names that my brain simply rejected upon hearing. Part of the game involves scouring the internet or YouTube for explanations of unknown systems that will allow you to modify that do-hickey or boost that character. Even more of it involves a spinning carousel of game show screens that reveal the loot from your gachapon levers. Scoop up all that fat from the top, and you’re left with a stylish but basic battle arena that you enter multiple times, set in a series of undemanding 2D mazes.

It doesn’t assist that you’re fighting in the same few spaces over and over again. For all the elegance of the world, there’s surprisingly little to explore. The most pleasant setting is the city block where you run errands (more on that later). But while the visual splendor of the zone is neat, it doesn’t make up for the boxy, uninteresting, and short-lived arenas you fight in. It’s a shame that a game with such graceful character animations is circumscribed to characters traversing the same few spaces in a deconstructed train station for hours on end.

In the previous article I mentioned that ZZZ was like this Souvenirs Persona 5 is gachafied, and the problem with that comparison (aside from the fact that the genres don’t overlap all that much) is that even in its most grindy moments, Persona 5 gave me a sense of motivation. ZZZ doesn’t go that far. This is where each player’s tolerance for the anime personality matrix will yield different results, but none of the characters particularly charmed me. A lot of their desirability seems anchored in their appearance, and the last bit is tied to their elemental powers or role in combat. Even the ones who get the most narrative screen time (the manic gunslinger Billy, the inept negotiator Nicole, and the emotionally unavailable Anby) feel less like characters and more like fully animated action figures. Maybe I just haven’t unlocked the character I really love yet (time to go pull!).

Maybe I’m being a bit reductive. Zed Zed Zed (Zee Zee Zee) has its strengths, too. The city block you wander around collecting daily scratch-offs from smiling huskies and topping up your coffee is a dazzling and colorful cityscape. I like the recurring visual motif of the cathode-ray television, the ever-present devotion to retro aesthetics exemplified by the main menu, which shows a television with a looping cycle of ads and bzzrping identifiers to greet you as a customer downloads the necessary updates. I like that you can check “Inter-knot” on your phone at the end of the workday, scrolling through user comments on news articles. And I like that you can get photos and artwork to put on a memory board in your bedroom (you live above a video rental store). The first photo you get on that board—of your geeky gang of pals eating together at a restaurant—gave me a occasional thrill of emotional connection with characters who otherwise make me yawn. It’s these human mementos that may be the real secret of desire in this game for some, not W-Engines, Bangboos, or any of those other weirdly named items.

Ultimately, though, my time in the Zone Without Zen (Zero) left me feeling uninspired. The tutorial treadmill is long, and everything in the story is ten times more convoluted than it needs to be. There are a lot of easy-to-miss details and dead-end menus where you can get even more loot. In a game that isn’t free-to-play, the design solution might have been to consolidate all the loot you can get into one place. But for some reason, that doesn’t feel psychologically right for gacha. So the result is dozens of little tutorials that interrupt you to show you which series of tabs and icons to click on to find a minuscule pool of loot to get in the corner, an overwhelming barrage of “learn this, open that menu, press this button, okay, now this one.” It’s a bit like getting step-by-step instructions on how to unbox from a really picky drug dealer.

It also includes all the usual linguistic obfuscations, countless currencies, odds and ends required to upgrade characters and equipment. For those who understand gacha grammar, it’s just a matter of learning some up-to-date vocabulary. For anyone simply drawn to the dazzling characters and scenes of a carefree cyberpunk world, perhaps looking for satisfying third-person combat, it’s less appealing. Just exploring and understanding the wild maze of menu screens takes longer than learning the basics of the action. This isn’t necessarily the final nail in a video game’s coffin. Many great games are all about menus, all the time. But to me, it’s the hallmark of an uninteresting third-person action game, no matter how visually or aurally stylish it may be.

When the term “juice” (or “game feel,” as it’s more commonly called today) was accidentally coined, it was offered as a reminder to make games more enjoyable for players’ hands, eyes, and ears, so that they can become more present, more grounded, even in an unreal space. Zenless Zone Zero uses the same principles to encourage the player to live too much in the menu screen. To me, that’s a deeply superficial world. A really nice pair of shoes that sit around the house, look great, but go unused because they’re uncomfortable and impractical to wear.