When I was little, I really liked what I saw of Shin-chan, even if it was mostly just glimpses of his bare ass on Japanese TV. He seemed mischievous, a little perilous, and part of a fun family vigorous. Fast forward to the present and I can only describe this boy as… annoying. At least to me, it’s the odd flag bearer for a series of games where you experience a nostalgic Japanese summer in the countryside.

And I think it’s doubly weird that Shin chan: Shiro And The Coal Town chooses to take a collective marathon approach, which doesn’t necessarily make experiencing the Summer of Cicadas all that mesmerizing. But there it is too massive but: I can’t stop thinking about it. Of all the games of 2024, Coal Town probably impressed me the most. In a way, I hope this applies to you as well.

Coal Town, like its predecessor, is a spiritual successor Boku no Natsuyasumi games (My Vacation). Where Natsuyasumi played a harmless adolescent boy who stays with his extended family in the Japanese countryside, Coal Town mirrors this setup, but Shin changes it. You are staying at a established country estate in Akita Prefecture, where you can fish and catch bugs and, above all, live in a pleasant way.

Except no, you’re not a nice adolescent boy, you’re Shin chan: a five-year-old who shouldn’t know the concept of horniness, but it always lives inside him and erupts every time he interacts with a woman (his family is also constantly horny, so it makes sense). Every time he speaks, it feels like broad mucus is coming out of his mouth, muffling the pleasant chirping of summer. Hold down the “run faster” button and it turns into a hovercraft spinning your ass (that’s a good thing, to be sincere).

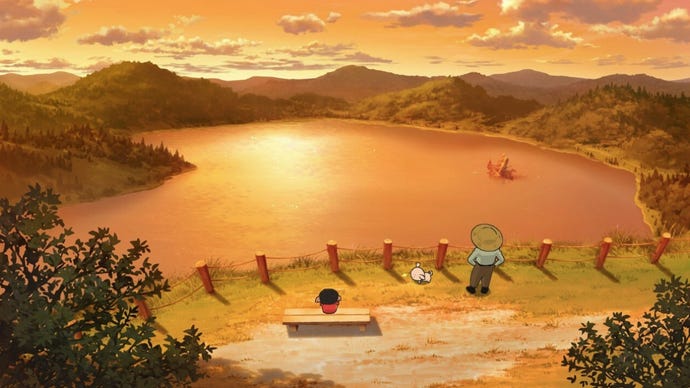

Being Shin-chan is annoying and a little exhausting at times. But the overall rhythm of the game is nice and illustrated with truly lovely graphics. At the beginning, the city is divided into easy-to-understand vignettes: an exaggerated shot of irrigation canals and rice fields, a cliff-top bus stop overlooking Akita, vegetable stands and lovely benches, and each room in a established house (genkan, tatami floors, sliding doors overlooking the greenery – all this brings back fond memories of my grandfather’s house). You run between these works of art, collecting wildlife and gathering herbs for the townspeople. And each time you move between spaces, time will decrease until the day turns into an amber afternoon and Shin-chan’s parents tell him to go back inside before it falls into the starry night.

No, Coal Town doesn’t play like Animal Crossing, in the sense that in-game time runs parallel to real time. Place Coal Town and everything will pick up where you left off, but the game has a similar philosophy to AC. You gradually create a daily routine that grows as your city grows. Once you collect antlered deer, shiso leaves and carp for humans, previously blocked paths open up. For example, children can go off a mountain path that leads to more people, more checklists, and rarer ingredients to collect.

Since progression is locked behind the activity of “getting things” which in many cases can take days to bloom, collect or appear, you should absolutely not play Coal Town during long Steam Deck sessions (runs like a dream) as I did in this case review. Like dipping your jam-covered hands into a picnic basket, this is a game that needs to be chewed in leisurely bursts, otherwise time-gating can lead to gorging too quickly and burnout.

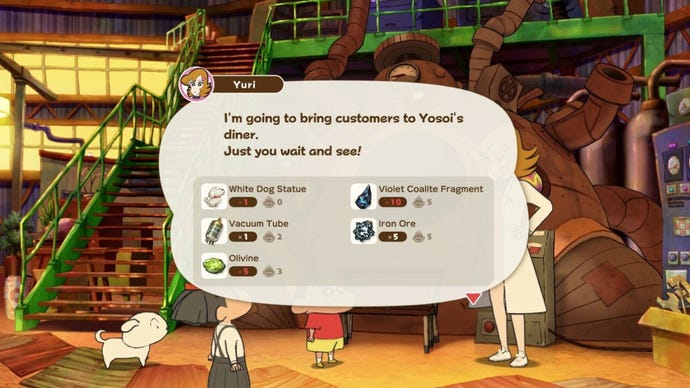

The collection does not end with Akita either. Sooner or later you’ll board a mysterious train bound for the once-busy Coal Town, which now lies mute and destitute. As with Akita, you can go to Coal Town at any time of the day to complete tasks for its inhabitants, collecting things other than wildlife: turbines, shafts, various gems and minerals. This is where many of your main quests take place, as you must provide a brilliant inventor with huge lists of things needed to rejuvenate the city.

Again, checklists can come in handy as you portion out each day to optimize your earnings as much as possible, and RNG gives you the finger. But once you have access to all of Akita and Coal Town, Shin chan becomes something of a clever economic tango. With trading stations (trade a butterfly for a fish, for example) in both Akita and Coal Town, you can find those elusive shopping list items via cleverly labeled links. For example, catching twenty granny ferns in exchange for some milk, which you can then sell at the Coal Town post office in exchange for a turbine. It’s undeniably satisfying when it all comes together.

The game partially realizes that you can’t just stuff Grandma’s pockets with cabbage, so it introduces trolley racing, which is a elementary mini-game in which you race against others in a trolley. The winner is not the one who finishes the game first, but the one who collects the most coins before the time limit runs out. Drive into your opponent, beat him in a lap, don’t accelerate too brisk on corners and you’ll score points. It’s a good time! But once again, it’s tied to the collector marathon. To win these must-have, more challenging races, it’s best to collect the parts needed to design your cart with chilly hardware.

So yes, if you approach Shin-chan like I did, the lovely art will eventually become a blur of color as you circle through each vignette with one goal in mind. Harvest the tomatoes. Trade corn. Roll up the eel. Ten of them in favour twenty of these. I said get the fuck out of my way, nice antique man, that fucking wheeler dealer has a place to BE.

Really, collecting bugs and more in Coal Town is an average experience, perhaps elevated to “perfectly okay” if you’re a checkbox freak. And yet I find that the game occupies a place in my mind that I can’t shake. I think it all depends on what this game represents, which is: the Japanese countryside deserves your attention.

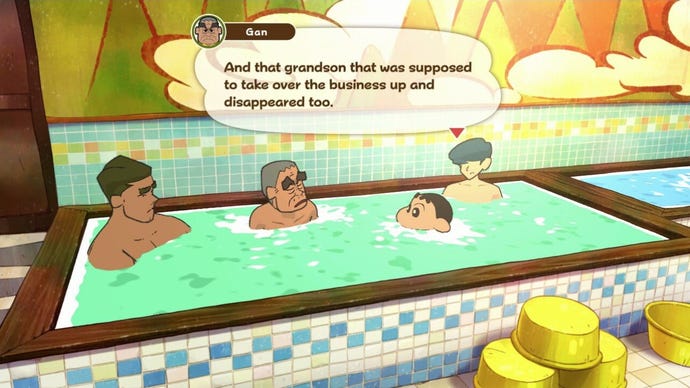

When I told my mother (she’s Japanese) about Coal Town, trying to capture people’s nostalgia for their Japanese summers spent in the countryside, she was right. “Many Japanese children nowadays won’t have this experience when they grow up,” which I hadn’t thought about before. In a way, my mother’s statement is quite unhappy, and almost certainly reflects Japan’s current relationship with the countryside. Relax in the onsen in Coal Town and you’ll hear a miner mention that it’s a shame his son moved to the city. Residents around Akita are surprised to see you, a guest of all things.

Of course, Coal Town is a representation of Japan’s forgotten rural industry. A rusty, shrinking community of people succumbing to the winds of change. For Shin-chan, this is reality, a place that he and his puppy Shiro explore every day. To adult family members? This is nothing more than Shin Chan pretending; dream. And as your presence as a member of the up-to-date generation lifts the spirits of both Akita and Coal Town with more visitors, revitalization and rediscovery of their history, you wonder – is it true? Allindeed a vain dream?

No, Shin chan: Shiro And The Coal Town does not pretend to find solutions to Japan’s social problems. Let us hope, however, that this will make more children interested in the countryside. Perhaps it will awaken in those who miss the Japanese summer a desire to rediscover it, a need to return and experience it again – and even share this nostalgia with loved ones. Maybe this will support everyone else discover at least a little bit of bright joy on the screen.

So whether or not the game is challenging, all things considered, it’s really great. And I know for sure that if I visit Akita, it will be impossible not to think about Shin-chan… and his naked ass.