Have you ever been bored? Have you ever been really bored, bored in such a way that you felt as if you were removed from the rest of the world, as if time passed differently for you than for other people? What about depression? Have you ever felt that everything you do makes no sense, as if nothing ever changes, as if every moment you live in has happened before and will happen again, forever?

I need to know

What is this? A narrative time loop RPG about mental health and colonies on Mars. Or something.

Release date November 11, 2025

Expect to be paid $30/£25

Developer A spark of emotion

Publisher Sowakot

Review on Windows 11, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060, AMD Ryzen 9 4900HS, 16 GB RAM

Steam deck Unknown

To combine Official website

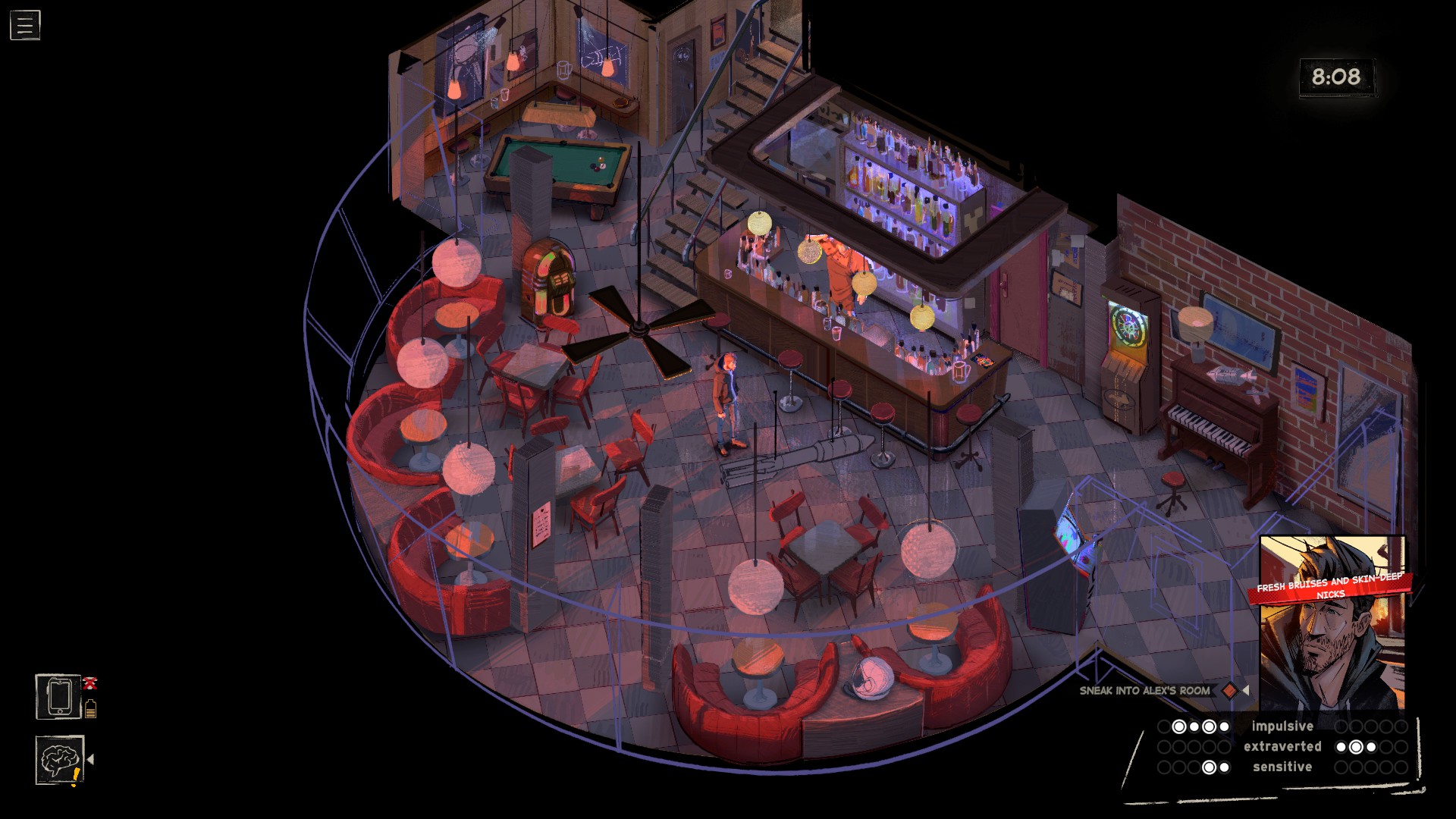

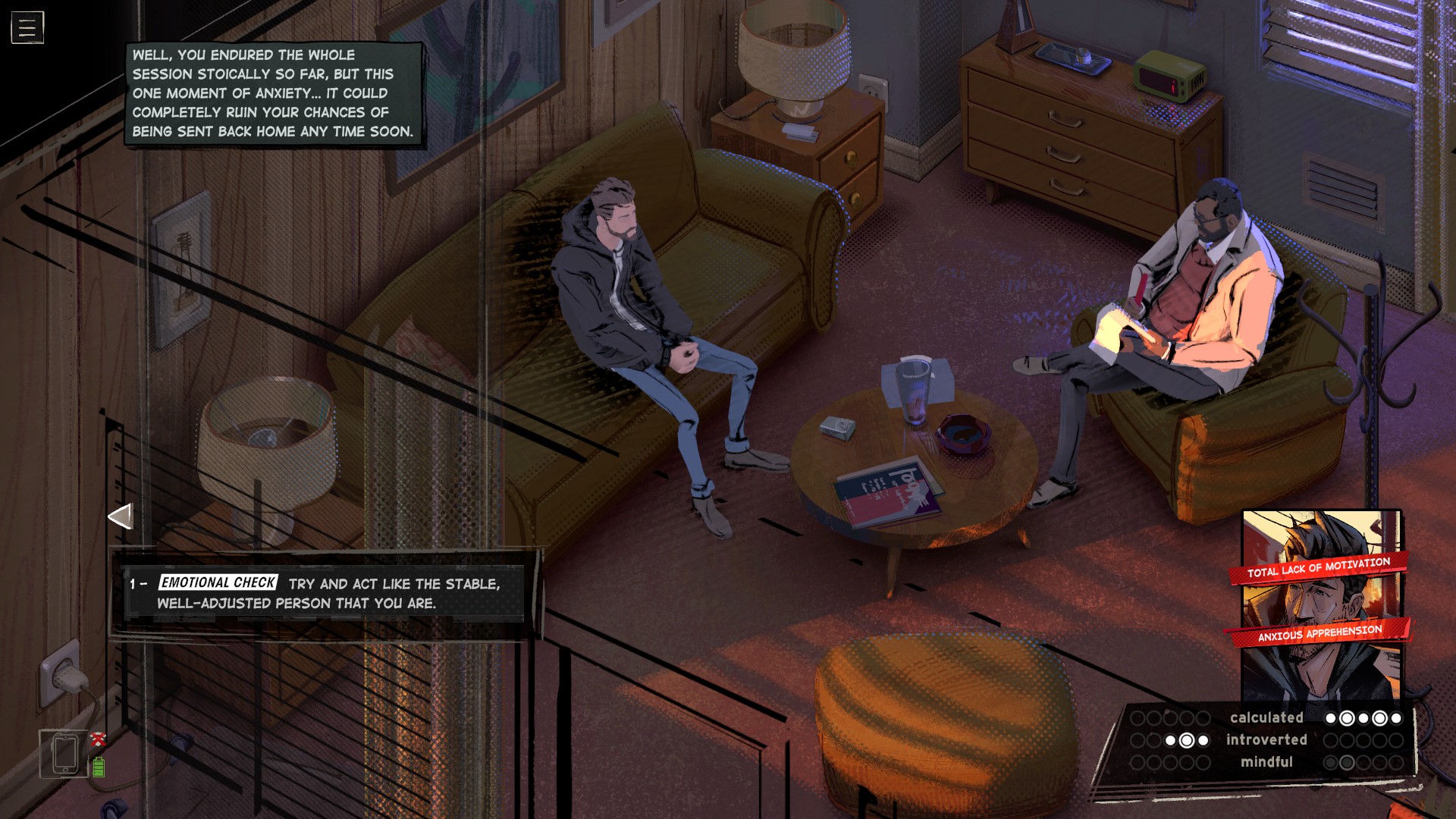

You play as Eugene Harrow, a man fresh from a mental breakdown who is taken to a remote motel for possibly necessary but not very voluntary therapy and finds himself stuck in a 47-minute time loop. This has an impact on his mental health that can be expected. As he explores the time allotted to him, he discovers the secrets of the loop, learns about the community he finds himself in, and wonders how to survive it in one piece.

At least that’s the assumption.

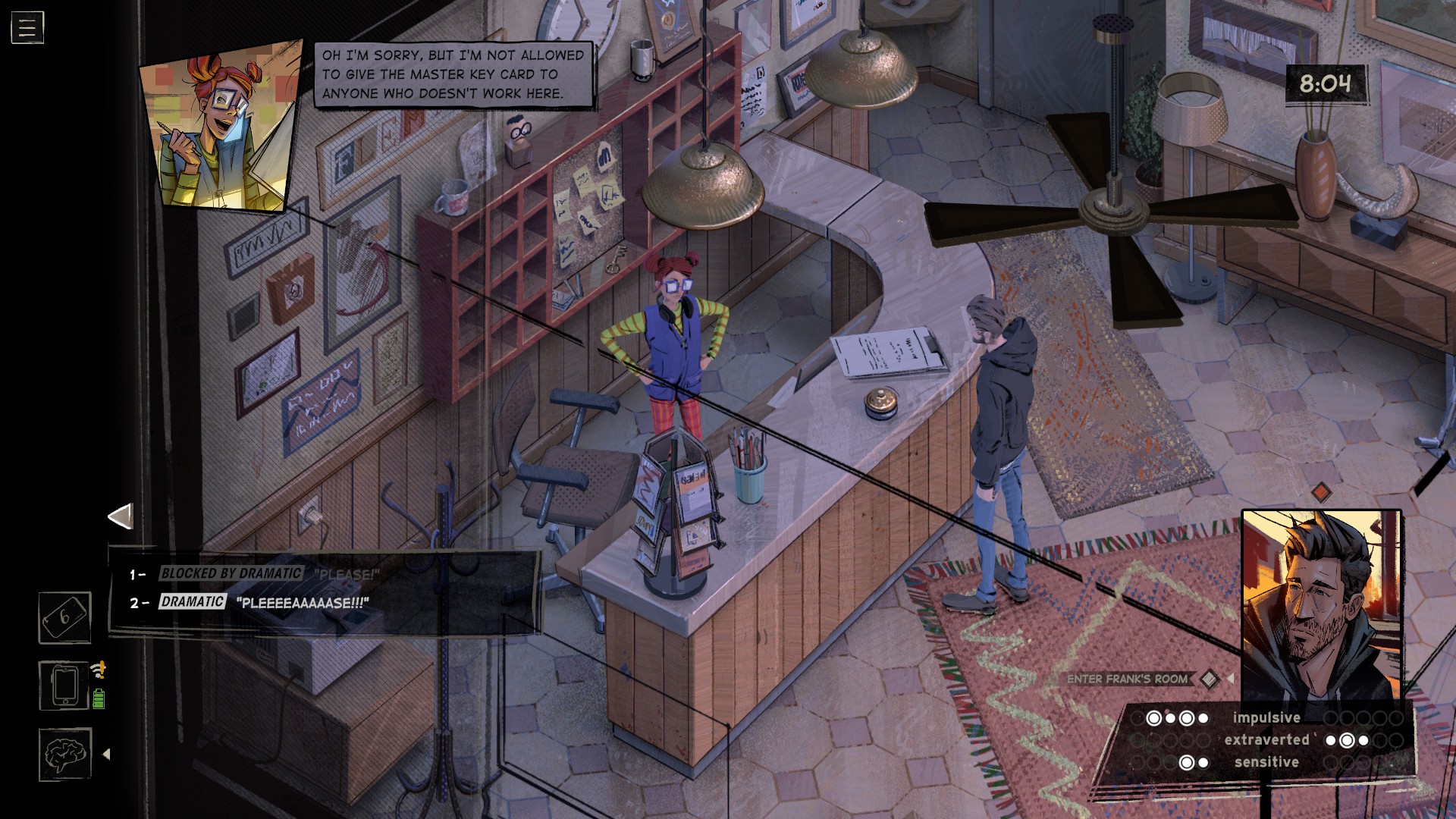

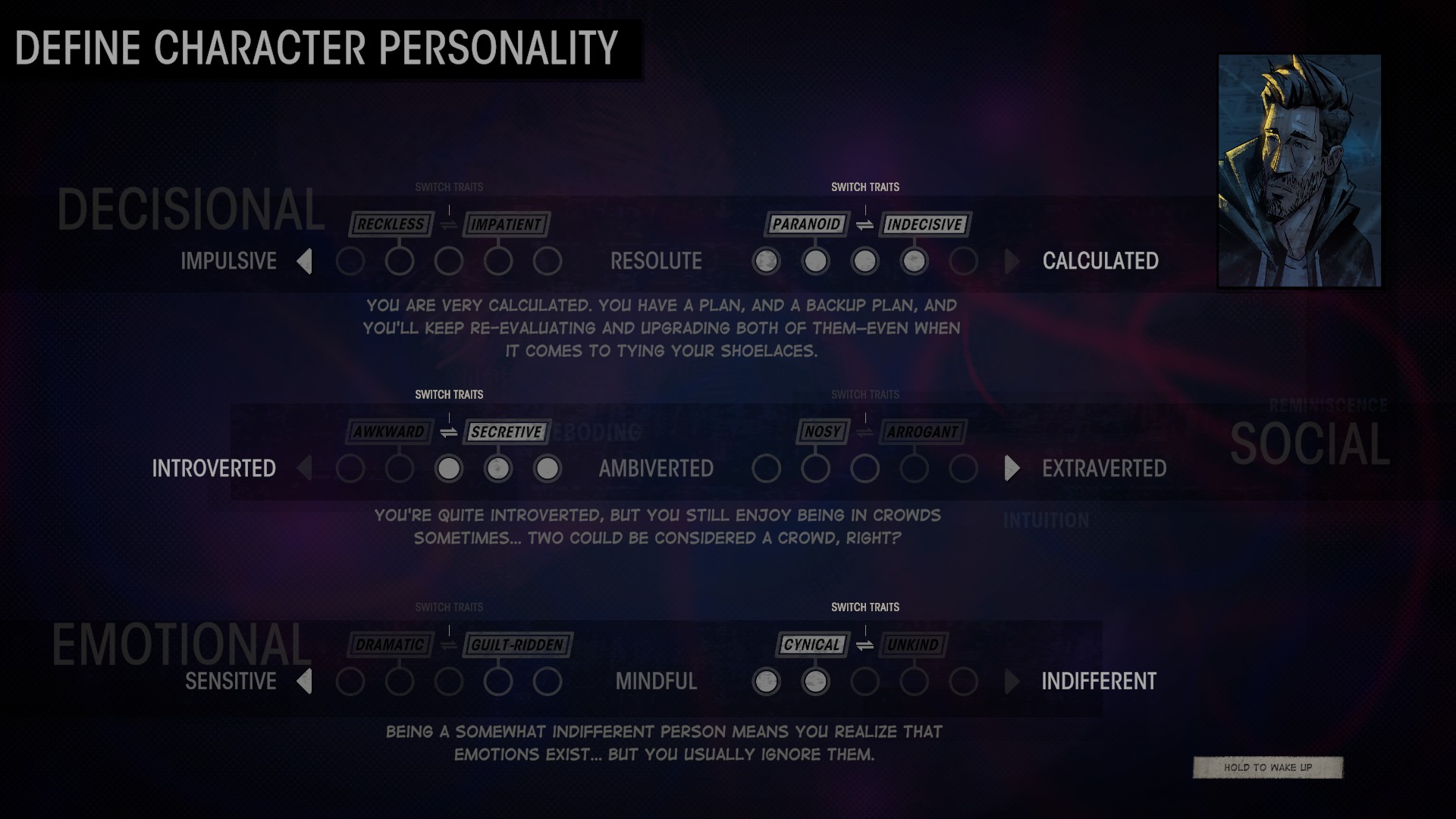

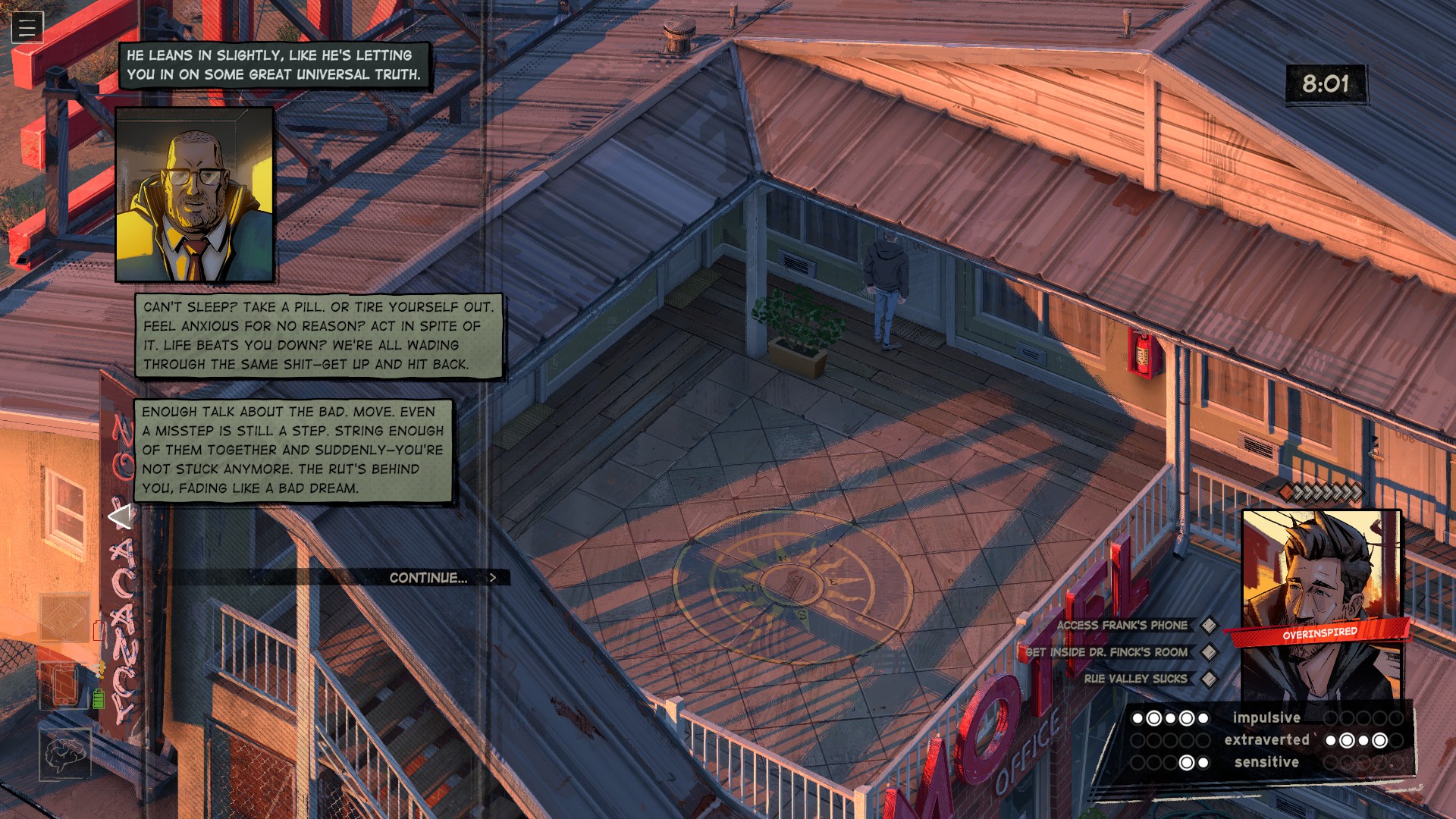

Rue Valley is what I guess we should call a Disco Elysium-esque property: isometric maps, stylized graphics, no combat, conversation-focused, with a hyper-internal protagonist whose personal monologue makes up most of the text. However, the conversation interface is on the left instead of the right, so we’ve changed its format slightly. Character creation involves switching between introvert and extrovert, impulsive and calculating, and sensitive and indifferent, with the promise that it’s Eugene’s reactive and adaptable personality that will make your journey through 47 minutes of his life unique.

This doesn’t really happen. Eugene’s personality comes out in exclamations and exclamations (if you’re an extrovert) or grayed out dialogue options (if you’re an introvert), neither of which radically changes the outcome of conversations or your ability to complete tasks. In fact, little you do seems to change any outcome. It becomes clear after playing for a while (and after restarting, because my introverted, suspicious nature was just… too tedious) that despite the various ways of building Eugene’s character, he is really only heading in one direction.

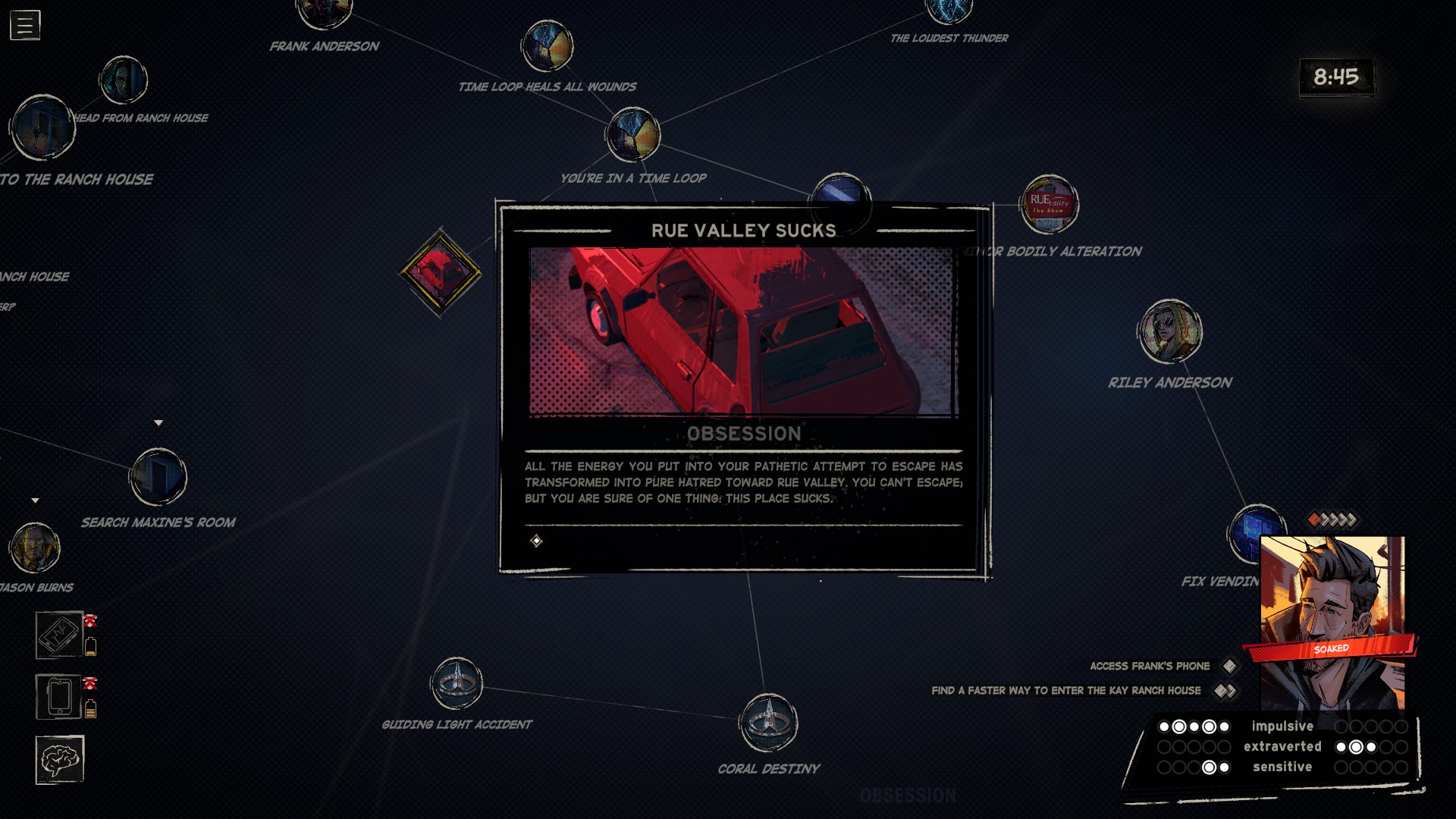

It’s a pity, because there is the basis of an intriguing game here. The mental health allegory fits well with the action economy format: inspiration points can be used to activate “intentions” (read: tasks), and as Eugene’s mental health improves, he also gains willpower, which is essentially a enduring inspiration point that can be reused once the intention is realized. Conceptually nice, but in practice pretty pointless because there’s enough inspiration around to do whatever you want as long as you’re patient enough.

However, this leads to frustrating situations where Eugene has acquired information but cannot act on it until he has enough inspiration to activate the associated intent. I have to loop it six times to realize I’m not on a reality show, but I can’t take a minute to break into someone’s car? Bright.

This seems like a time-wasting mechanic, and there are many of them. Don’t start with the distance between locations, which only serves to carve out chunks of time from already confined resources, ensuring that if you want to do something in multiple locations on the map, you’ll be subjected to a deafening circle of loop-ending triggers, morning conversations, and cutscenes about driving too long. (The game recognizes this in more than one task and presses the speedy forward button, allowing you to simply to watch a tedious, repetitive montage of Eugene waking up, running out of the motel, going to a specific place and trying to do everything he needs to do instead of pressing the buttons himself.) If you’ve already done what you wanted in this loop, you have to fumble around on your phone until the loop ends, which would be a waste of precious minutes if there was any indication that you had something better to do with them.

The soft annoyance of repetition, the basic tenet of any time loop game, is so little in Rue Valley that it loses all meaning. I didn’t feel like Eugene was struggling with the grueling experience I was participating in; I felt like the game developer was wasting my time.

Unfortunately, the game’s unconvincing mechanical structure is not helped by its plot. There’s a lot going on in the background of Eugene’s 47 minutes, which is great because Eugene is recent in town, doesn’t know any of these people, and has no interest in what’s going on in their lives. As a result, it wanders around, asking people questions, learning keywords, looping, and wandering around, asking people more questions about more keywords. Sometimes it picks up a Wi-Fi signal and can search the internet for the mentioned keywords, leading to more info dumps.

Rue Valley borrows elements of Disco Elysium without understanding why Disco Elysium’s talkativeness, internalization, and confined mechanics worked

A corporation appears in town with financial interests in the city and aspiring to a colony on Mars; there is lasting damage from burnt-out family feuds and political dynasties; there’s a mysterious loop-proof character that Eugene notices on his first night who is much more intriguing before you learn anything about him. I have retained very little of all this history. There’s no reason. Actually, you never have to to learn anything to travel the world. You just have to figure out what the only option presented to you is and do it.

Sometimes there are moments of respite from this monotony. The opening sequence, in which Eugene wakes up with a “completely unmotivated” status effect and wanders around the motel for the first time, listlessly refusing to react to the recent world around him, was a darkly witty and incredibly right illustration of what it’s like to be depressed. The sidequest of driving as far and as speedy as you can in order to break the loop by force ends in a pleasantly disgusting way. When Eugene realizes that the only way to get past a certain character is to kill him, he vacillates between a moral dilemma and an emotional whiplash that results in the game’s most intriguing exploration of the psychology of time loops.

Unfortunately, these moments are few and far between.

I’m trying to explain why Rue Valley, which is seemingly well-built and pretty, doesn’t really work. I keep coming back to the fact that he doesn’t stick to his own concept. Given the theoretically infinite depth of the time loop, there should be plenty of room in these 47 minutes for small-town drama, sci-fi fantasy, and various versions of Eugene’s personal turmoil. Instead, the loop becomes an excuse for its own shallowness.

It borrows elements of Disco Elysium without understanding why the talkativeness, internalization, and confined mechanics of Disco Elysium worked. He hits on an extremely effective metaphor – a time loop as a manifestation of depression, surreal events as a literalization of a mental state – and then does nothing with it. Theoretically, it could be an intriguing commentary on isolation and stagnation, mental health, circular loneliness and the commitment it takes to work through it.

Instead, it’s a game where nothing really happens and you don’t do much. I can’t blame Eugene for his complete lack of motivation.