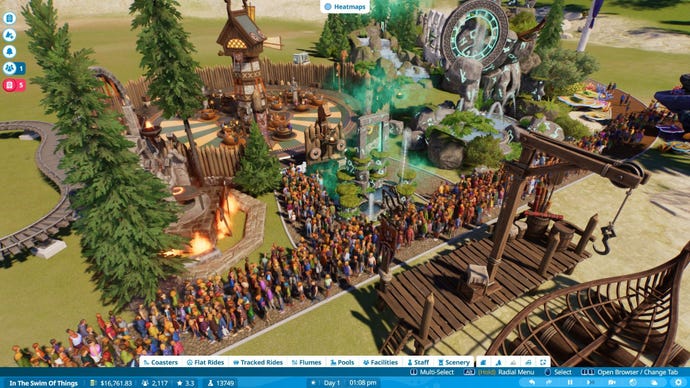

The Planet Coaster amusement park management simulator involved creating roller coasters that would push park guests to the brink of vomiting overpriced burgers, while also providing a high level of thrill on twisty rides. Planet Coaster 2 wants to do it again, but this time it adds water parks to the mix, with slides to design, swimming pools and raft rides that can be combined to create challenging, high-speed spirals. You can feel a sense of imaginative pride when you look at the water wonderland you’ve created with these tools. But you may also wonder if it was worth it. As a newcomer to planet management games, I found this shaky sequel complicated, cumbersome, and poorly explained.

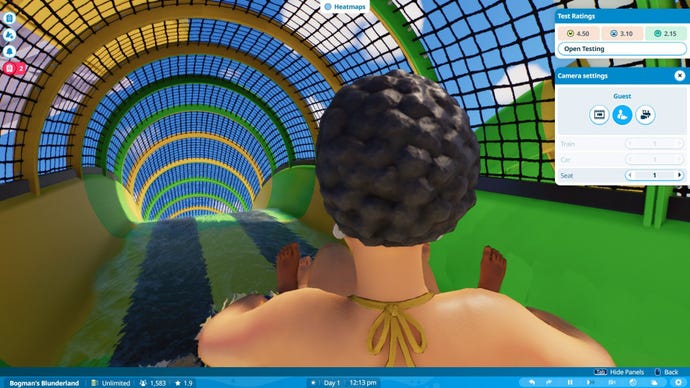

The large advantage is the modular building that you can make. Basically, you get a library of individual menu items and you can combine them to create novel buildings that house guest toilets, changing rooms or pizza stands. This also applies to the park’s decorations, with a enormous section of the menu devoted to trees, rocks and props reminiscent of Vikings or classical architecture. What’s more, each slide and roller coaster can be built piece by piece, twisting and turning guests’ heads to suit their whims.

It’s a good idea on paper. I like to drag and crush comet vomit or manipulate jets of water into increasingly risky spirals – it’s a good way for me to operate my imaginative time. However, squeezing uncomplicated drinks shops into prefabricated housings to make them a bit more presentable seems like a tedious job, hampered by menus that are cumbersome to navigate.

For context’s sake, I usually love building and crafting things using gaming tools (for example, I created entire maps in Halo’s Forge mode). And my previous hands-on experience with this addictive sequel had me excited to create my own fun-loving Aqualand. However, upon deeper play, I find there’s something fundamentally unintuitive about the menus and UI that makes learning and understanding the game’s many quirks a pain. At any point in Planet Coaster 2, I’m not sure which part of the screen I need to click on.

There are YouTubers who do good work explaining all these thingsbut that doesn’t stop me from finding it a chore to correct the odometer and check off the boxes. Those who are more committed to the water park of their dreams (or those who are more familiar and patient with the user interface of Frontier’s other Planet games) will get more out of it. But even they may wonder whether it’s worth losing the many other thematic elements from the first Planet Coaster that have been omitted from this sequel, presumably so they can be sold for DLC later.

Still, you don’t have to create things yourself with a click. Instead, you can press the enormous button labeled “Border Workshop” to scroll through other players’ creations, all available for download. You’ll find, for example, huge roller coasters that dive into the mouth of the Arrakis sandworm, or the ornate facade of a Roman bathhouse ready to be filled with your choice of wave pools and diving docks. But even this archive of filtered goods feels like a more clunky version of what players of the previous game enjoyed via the Steam Workshop.

The campaign mode (often where management games like to hide their tutorials) spends more time shooing away wayward characters with family chats than actually showing the ins and outs of the UI. Characters will share jokes, flirt, and – for some reason – develop a deep understanding of the Planet Coaster universe. I understand the need to add some cartoonish personality to a genre that relies heavily on numbers and large picture planning. But it also slows down the flow of useful information (your goals or learning goal) as you wait for a surprisingly enormous group of characters to finish their little skit. You can skip their chat, but then you’ll be none the wiser Why you do any of the things summarized in the goals menu.

Ultimately, most campaign missions are not educational exercises at all. And if they do, they become increasingly awkward, resulting in confusion and a lot of guesswork when exploring the menu. It’s often unclear what the game expects of you, and the freedom it gives you in these scenarios is so varied that you end up running into artificial constraints when looking for a solution. You may be tasked with completing a roller coaster that is missing some parts. However, you cannot edit or delete parts of an existing song, you can only add novel ones. Another task might be to place a novel roller coaster. But you have already filled all the available space with the flat passes from the previous task. Can I buy novel land? No, this is not allowed yet. The real solution is to individually knock down every tree and every rock in one tight spot and squeeze the vehicle into the remaining space.

This holding back of certain features is likely the result of a campaign to teach you the various build tools in a piecemeal fashion. More often than not, however, you end up feeling like the game wants you to play the “right way” without clearly defining what that right way is. Imagine an art teacher who puts 30 paintbrushes in front of you and says, “Art is about creativity! Let’s learn!” then, when you reach for a broad brush, they say, “Not that one.”

The game’s penchant for micromanagement takes over some tedious aspects elsewhere, like having to navigate to each guest services kiosk’s menu and click “open” before it actually does its job. What does this extra step add to the game? Sure, it’s only three clicks, but it’s the same, joyless three clicks every time. Testing rides before opening them makes sense, but does a burger stand really require a grand opening every time you build it?

The entire intricacy of the campaign caused me to abandon it early in favor of the sandbox mode, where you can thankfully give yourself infinite cash and choose whether or not you want to bother with power grids and water filtration. By default, you simply have to place these generators and pumps throughout the park to spread a color-coded glow that means there is enough electricity and neat water in your pools and attractions (imagine the basic water and electricity maps in Prison Architect, but with less need exactly). I played with them on because I like to think about it all in layers and look at the game’s visual heat maps that show where your power grid is missing or where the pools are probably full of pee. However, you can completely disable these game layers, at which point your sandbox will just do it Work. This is a tempting prospect for those who just want to make things look nippy.

I had fun in the sandbox mode for much longer than I suffered in the campaign. Here I enjoyed creating winding paths for guests and dealing with crowded bottlenecks by luring them along a different route filled with stands full of balmy dogs and inflatable toys. I was especially content when I accidentally planted a huge collection of trees in the jungle and then used them to create a “swamp” of winding pools for guests to wade through and discover my newly launched water slide. It’s moments like these that the imaginative potential of the simulator truly shines, and I could understand exactly why people put so much time and effort into their creations in the Workshop.

However, over time, the weight of the impoverished UI eventually overshadowed my enthusiasm for it. I’ve been playing management games for a long time, and I find it strange that Planet Coaster 2 makes me feel so stupid. The method of building something as uncomplicated as a set of toilets is complicated and sticky, and requires returning to the side menu so often to resize meshes or change angles that my brain just starts to reject it. Like I said, more patient Planet fans may feel less pain with this cumbersome interface. If this is you and you want to risk a face full of chlorinated sliders, dive right in. However, for novel players like me, it’s a painful flop.