Hmm. Hmmmm. Okay. So what do we have here? I have a Blood Donor card that lowers the value of the hearts I play, but it also heals me. That’s fine. The lowered score means I can push another card for more healing. If I draw a Tarot card, I’ll deal damage with each healing, and I’ve already drawn two Scratch Cards to deal even more quick damage. Now, if I just draw Jack, I can put down King of Space and Time for a brutal finisher. That shifts everything on my side to my opponent’s side, forcing a beatdown to deal a nice final bit of pain and…

Oh, you thought we were playing Blackjack? At one point, I was too. These were much simpler times. Before the NFT monkey. Before the bug cards. Before flippin’ Charizard. Whatever other issues I might have with it, I can’t praise the shuffly-slappy strategy of Dungeons And Degenerate Gamblers enough for taking Blackjack – a game that’s only mildly compelling if you happen to have your favorite leg up on it – and making it engaging without changing the fundamentals beyond the point of recognition. Changes almost everything else beyond that point, mind you. But even when you’re burning a Necromancer library card with your Gerald of the Riviera, the down-to-earth desire to risk it all on a single card for a slightly better outcome remains mighty. I think I could appreciate Blackjack more now, to be straightforward. D&DG makes us realize how solid those foundations are, holding their shape even when creatively trolled and attacked from all sides, like the canvas in a Lawler vs. Kaufman fight.

It would probably be more fair to say that D&DG is the game that changes these fundamentals and does the most work. Like established Blackjack, the goal is to get as close to 21 as possible without going over. You take a card, and then you can either stick with your current score or have a different one. You’re pitted against a group of opponents. One of them might be the goalie. The other might be a talking rat. Whoever gets as close to 21 wins the round. The first twist on D&DG is that losses don’t affect your chips – they affect your health. If you stick with 17 and the rat gets 19, you lose two health. But if the rat goes over 21 – again, you deal damage equal to your entire score.

But you may want to continue at this point, even after seeing your opponent lose, so the health system cleverly encourages risk even after achieving a established Blackjack victory. The stupid rat loses when you’re sitting on 16, but he has 17 health left, so you may want to risk another draw to finish him off before the next round starts, or maybe it won’t go so smoothly. In this way, D&DG emphasizes the importance of not just winning, but winning All right.

You only have 100 health points, and your opponents often have between 30 and 50, so busts can be devastating for both sides. To assist you, each opponent displays the number they’re standing on, allowing you to plan around it. If either side hits the magic 21, their score gains bonus effects based on the suits that make up it. If you hit a 21 with 10 clubs and 11 hearts, you deal double damage with clubs and also heal 11 health points with hearts. Spades generate a shield that is lost before health when you’re damaged, and diamonds generate tokens.

All of this applies to your opponent as well. The cherry on top is a system called advantage, which is basically cheeky, cheeky cheat points. At the start of each run, you’ll have a quick tutorial match, after which you’ll choose between two advantage tokens with different rules. One might generate an advantage point every time you win a round, while another gives you one every time you stand on a score of 17 or higher. Advantage is accumulated throughout the match, and you can spend it at any time to employ certain cards for special effects. Often, these cards are “on hand,” meaning they go into your hand rather than on the table when you draw them. Many others are base-value cards that either change their effect or provide an additional effect when used.

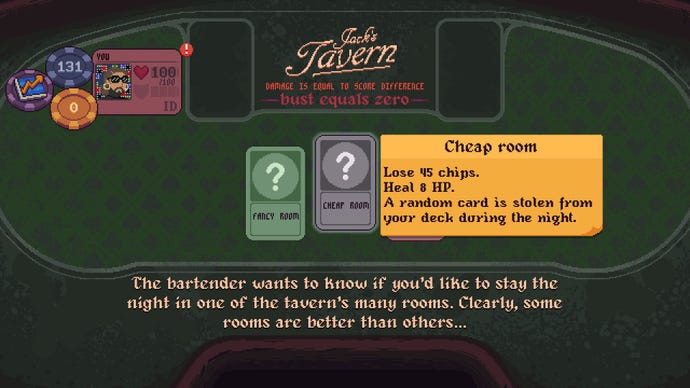

Despite being relegated to some kind of auxiliary scoring system, tokens are still incredibly useful. After each opponent, you’ll be given a choice of four cards from which you can choose one. Only three are observable, and you’ll have to pay 21 tokens to look at and choose the fourth. You can spend them on a fancy hotel room overnight, which will give you some health. You can pay a forger to change the value of your cards, and sometimes you’ll have the opportunity to simply buy more cards.

And they, in a very broad sense, are the brakes. What really makes the game, If Breaks: Various keywords and other weird effects that you’ll accumulate and strategize, creating searing combos that can withstand later opponents. Because you can bet they’ll be breaking things too, and doing so in a thematic way, no less. A Necromancer can hit you with a bunch of Gravecards that can be used to lower his score, ruining your plans. A later opponent might have a deck built specifically to pile on extra points on your side once you’ve stood, so you’ll need the right counters.

This reliance on themes – and what are almost certainly opponents’ set plays rather than true randomness (or at least decks built to make certain plays very common) – is a substantial part of how the game stays compelling, and often quite fun. But this is also where my problems start to show up. Take the stage 2 boss, for example. He often likes to play “21 of Clubs”, which is an instant win or at least a draw. There’s an basic counterplay here. You just have to find one of the few cards that sets his limit to 20 and he’ll keep losing. I’ve beaten him without that card, and there are other ways around it. But I think it’s symbolic of a certain level of railing, or at least regular deck checks, that I usually know well in advance whether I’m going to be prepared. It gives you milestones to work towards, keeping the drama going, but it also meant that sometimes I started to see defeat coming very early. Hell, sometimes I knew after the first few games.

So you end up with this feeling of being confined and at the mercy of fate hanging over every game from the start. So I win games and play events, hoping against hope that I’ll get lucky with the right cards. Because there’s a point in the series – not too far away – where playing the basics just isn’t enough. You’re going to need certain cards, or at least that’s how I felt. Full disclosure: I’m a math idiot, so it’s entirely possible that there are some deeply insidious safeguards that allow for guaranteed killer decks in every series. Either way, I rarely land on them, and what initially felt like freedom didn’t last long, shed its Scooby-Doo mask, and reveal itself as some kind of daunting constraint.

And yet I’ll still play D&DG. After about eight hours, my collection tells me I’ve only seen half the cards, and discovering a up-to-date card is often a real pleasure. I also have a lot of opponents to beat, and starting decks and modifiers to play with. I won’t say that D&DG makes losing fun. Playing those early stages over and over again quickly loses its appeal, apart from the chance to land a deadly combo early on. But it makes losing bearable, and winning is great, and gets better the more you embarrass your opponent. Consider the game’s real promise, the fantasy at its core. How much can you make that talking rat regret his life choices? That’s still a fantastic sell.

This review is based on a test version of the game provided by the game developer.