Computers have always been, in a sense, animal wells. They are a haven for creatures of many shapes and degrees of literalness, down to metal. As in ecology in general, the most numerous and widespread are probably insects, starting with a moth that flew into the Harvard Mark II in 1947 and ending with the teeming contents of your average free-to-play changelog. A little further up the food chain we find “worms” like Climber who once attacked the ARPANET network and “wafflesa directory/client system written in 1991 for the University of Minnesota. There are computer animals born of branding—fire foxes and chirping birds and anonymous beasts that haunt the margins of Google docs. There are computer animals that are implied by the verbs we apply in computing—take “browser,” from an Old French word meaning to nibble on buds and shoots, suggesting that all state-of-the-art Internet searches are herbivorous in nature.

Billy Basso’s Animal Well feels like a celebration of all those unreal organisms, their whimsy, their weirdness, and their persistence across layers of technological change, as well as the more explicit, quasi-Jungian animal characters and symbols we find in video games from Zelda to Fallout. I don’t want to hide the beginning in fancy parallels here, but it’s also an absolutely brilliant metroidvania platformer, and a game that manages to be both deeply intuitive and completely, completely mysterious.

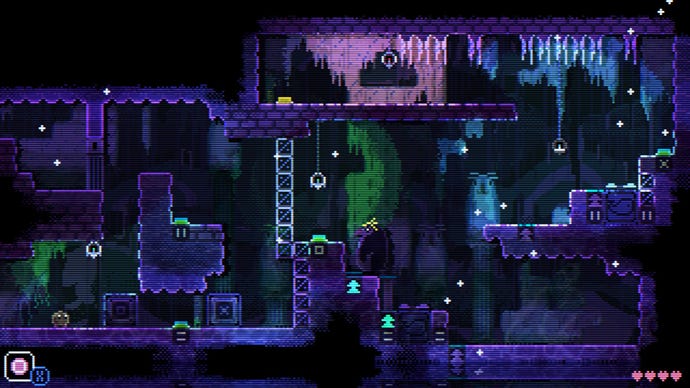

In Animal Well, you play as one of the simplest, most adaptable, and most adorable forms of wildlife in video games—a miniature, spongy ball with diminutive limbs and perpetually startled eyes, a lesser-known Kirby species without his substantial mouth. You’re dropped without introduction into a sepulchral but growing 2D cave system of dripping pixels, swinging blue lanterns, and countless, imposing statues.

Your initial goal is to collect some things from the four corners of the map, saving your progress on the age-old telephones that decorate the world and which, along with the floppy disk icons for saving, anchor the project as a love letter to the pre-broadband era. In doing so, you’re transported into a world of different groups of animals, some helpful, some hostile, with traits and behaviors that play into elegant single-screen platforming puzzles involving doors, pulleys, switches, and buttons. Along the way, you’ll find tools—though “tool” seems like the wrong word for something like a frisbee or a bubble wand—that are both directly applicable to the immediate obstacles and affluent with more elaborate uses that you’ll discover when you revisit these areas an hour or two later.

Finding the first four of these fascinating toys is, in my opinion, vital to collecting all the Stuff you’ll need to get to the end credits, so you can expect a fair amount of the usual metroidvania backtracking when you hit an impassable barrier. There are also no checkpoints, so you’ll often have to backtrack a few screens from a save room after your emoji wanderer falls into a pit of spikes or a cloud of boiling purple faces.

Animal Well has more friction than you might expect from a game without combat and killing. The more advanced puzzles require you to think beyond the confines of a single screen, considering how machines might connect in a biome, and it’s in these more scattered areas that you’re most likely to stumble and have to retrace your steps. But Animal Well isn’t all grind. Health-restoring fruit is usually a few jumps away, and while there are terrain hazards, most notably dim labyrinthine chambers where you’re chased by something resembling Pac-Man, you never take damage from falling into water – a concession to setting the game in a world that strongly reminds me of Sonic’s Labyrinth Zone. And then there’s the all-important question of the jump, which works brilliantly whether you’re precisely swinging between perilous surfaces, mashing buttons to scale a ladder-like cliff, or taking a leap of faith into what you hope is a hidden chamber (and there are dozens of them).

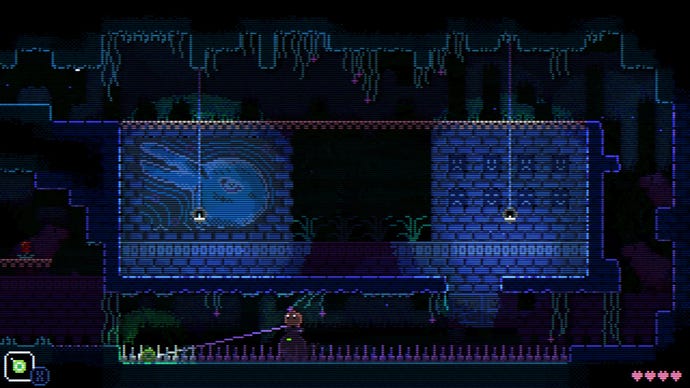

Beyond these broad outlines, I’m afraid I’m giving things away, because Animal Well does an incredible job of teaching you things and pointing you in the direction of other things without resorting to text. It’s this wordlessness that makes it so enigmatic, one that can keep you occupied for much longer than the 5-10 hours it takes to finish the initial run.

There are more obvious hints and clues – a squirrel that always runs off-screen, gargoyles whose eyes delicate up under certain conditions, and, most of all, the irresistible force of the next puzzle. But there are other sights and sounds that take a while to get to you, things you might want to return to after the credits – which, according to publisher Bigmode, means you’ll have seen about half of what Animal Well has to offer. Some of these tardy reveals remind me of Polytron’s Fez. Among the things you can discover is a pencil that you can apply to scribble on the game’s map, and suffice it to say that this is a game you might want to take notes on.

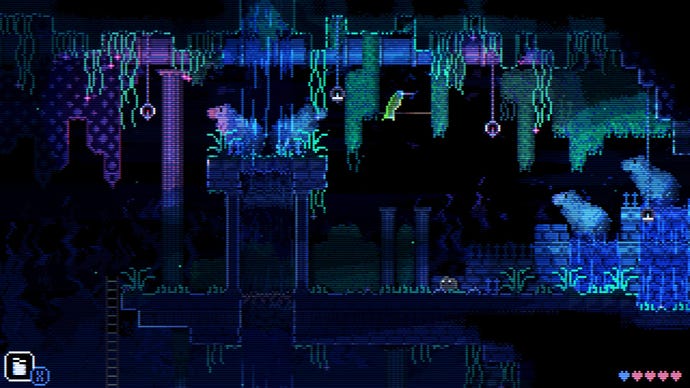

Again, I don’t want to give too much away. I can, however, tell you a little more about the animals, which range from giant geckos to nightmarish ostriches to uncomfortably boisterous dogs. If the puzzles make me think of Fez, then the creatures in Animal Well are reminiscent of Rain World, but there’s no tangled predator-prey ecology chasing you between screens, and much less the stark Darwinism of your relationships with other creatures—though there are certainly a few that want to eat you.

They are animals that are clearly video game creatures, rather than attempts to simulate a flesh-and-blood creature. They share many of the traits and weaknesses that are recognizable in everyday life, like the way a panting dog freezes when it senses something nearby, or the painfully sluggish movements of a starfish. But they have other abilities that make them descendants of other computerized creatures—the fauna and flora of Metroid and Oddworld, and more recently, Amanita’s Creaks and even Subnautica.

They create a spectrum of naturalism in dreams. Some creatures are little more than animalistic platforming elements, like the ghostly mouse heads that roll vertically and horizontally. Others are miniature animated portraits, like the giant capybara you see lounging in the background. A few of these animals have more sophisticated behaviors that suggest lives beyond their function for the player, but most are clearly mechanical, yet somehow charming.

How should what do we think of them? Mixed, I think. Pleasantly on the edge, perhaps. Playing Animal Well reminded me strongly of John Berger’s elderly 1977 essay “Why Look At Animals?”, in which he argues that animals have been excluded from human life under capitalism in proportion to how widespread and commercialized animal images have become. There is no way to reclaim what Berger calls the age-old, totemic companionship between humans and animals, because our methods of observation, representation, and circulation always hide animals from view. “They are the objects of our ever-expanding knowledge,” he writes. “What we know about them is an index of our power, and therefore an index of what separates us from them. The more we know, the further away they are.”

I have no idea what Berger would make of Animal Well, or of representations of animals in video games in general, but Basso’s game feels like a gentle, cyberpunk response to his conclusions. It takes as its premise the idea that animal images have excluded animals, and explores how our technologies of knowledge production and representation may have become animalistic in response. Above all, the game’s confusing, hybrid essentiality manifests itself in the way these animals sound. Sometimes they scream like beasts that have become software, with moans, barks, howls, and hisses that seem mercilessly sampled and distorted. And sometimes they scream like software that has become animalistic and disobedient because it has been kept underground for too long.

This review is based on a copy of the game provided by the developer.